Let It Get Back to Being

In 2022 director Peter Jackson released Get Back, a fly-on-the-wall documentary about The Beatles assembled from footage filmed and supervised in 1969 by filmmaker Michael Lindsay-Hogg. The latter’s task was to document the band attempting to record new material and eventually to perform a live concert for the first time since 1966 – although the details surrounding what that concert would look like at the time or even where it would take place were hazy at best.

Still, Lindsay-Hogg let the cameras roll and roll, first within the cavernous Twickenham Film Studios and later as The Beatles labored away in the basement of their Apple Corps headquarters in London. How much film rolling was involved? When Jackson’s Get Back was released across three Blu-Ray discs, the running time was nearly eight hours, though Jackson lamented not having the opportunity to release a far-longer effort delving into even greater detail.

Eventually, Lindsay-Hogg emerged from the chaos with a movie titled Let It Be. Released in 1970, the final summation of his efforts was an attempt at coherency assembled from the miles of film footage depicting occasionally frayed personal relationships framed by engineer Glyn Johns’ valiant attempts to record an album. By the time the film was released, The Beatles were no longer a functional entity, and within just over a decade Let It Be had gone out of print.

Let It Be, missing in official commercial action since the VHS days… That doesn’t stop the bootleggers, of course.

Now, in 2024, Let It Be has been revitalized and, though not yet available on physical media, the film did begin streaming on Disney+ last month. The question becomes: is Lindsay-Hogg’s original effort still relevant in the wake of Jackson’s far more expansive analysis?

Conveniently, this 2024 presentation of Let It Be begins with both directors discussing their work and events that have ensued over the years.

The most obvious contrast between the two efforts is the emotional stance presented by the directors. In Lindsay-Hogg’s film, there is an overall feel of optimism, despite a handful of moments of tension. In Get Back, the tension is the documentary. The occasional moments of humor or good will are desperately needed breaths of fresh air in a claustrophobic creative environment where four men know each other all too well.

The skeletal versions of some songs in Let It Be are mere bones in Get Back, riffs or pieces of progressions still seeking musical cohesion. And yet for some viewers (author disclosure: guilty as charged!) that is the expansive beauty of Get Back, a clearer, far more detailed look at what happened, how it happened, and why it happened.

The multi-hour endurance test that is Peter Jackson’s Get Back. Heaven or hell depends upon the viewer’s constitution and patience.

For those who have luxuriated in Jackson’s documentary, perhaps the most shocking thing about Let It Be is that it seems impossibly brief. And yet that brevity is a fundamental aspect of a film that was made for a commercial market of movie goers and general rock music fans, not sonic archeologists.

Obviously entire chapters of the whole story are excised from this shorter film. For example, in Let It Be we see The Beatles performing material on the film studio soundstage, before they miraculously appear walking onto the roof for their final concert above the streets of London. Not depicted is The Beatles’ decision to depart Twickenham Film Studios and migrate their recording efforts to the bowels of Apple Corps headquarters in London, naively believing they would be able to use a brand-new recording configuration devised and installed by self-proclaimed audio expert “Magic Alex.” Sadly, there was nothing magic at all about the work of Alex, with the basement studio almost instantly revealed to be an unusable disappointment. Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick, consulting with producer George Martin, was tasked with creating a functional multi-track studio for the band to use in their headquarters, essentially on the fly.

And even greater seismic ruptures – like George Harrison temporarily quitting The Beatles – do not disrupt the determined course of Let It Be, the bad blood not flowing in Landsay-Hogg’s final cut.

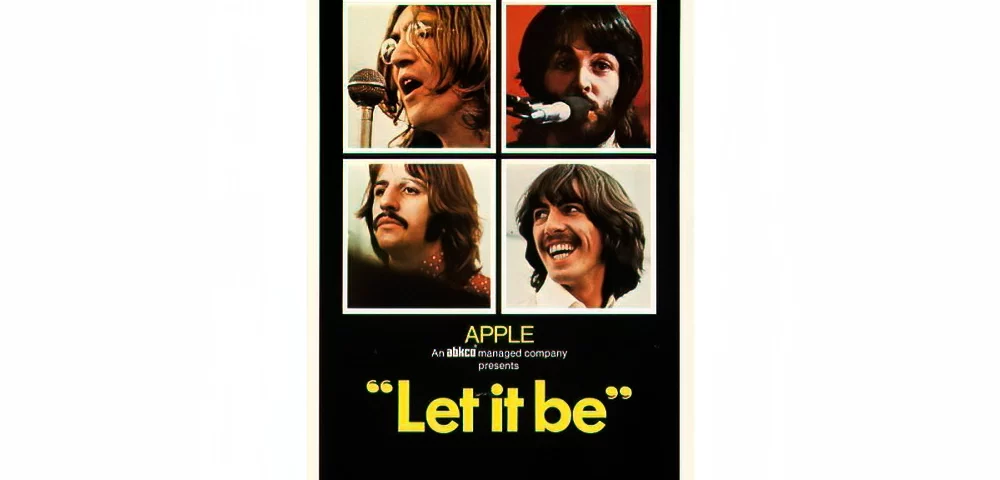

An original Let It Be film poster from 1970, promising a “bioscopic experience with The Beatles” – and in the end, less conflict.

Still, as something of a greatest hits depiction of a sprawling and troubled creative process, Let It Be is well worth seeing. That’s particularly true in light of the understanding that this film was approved by The Beatles themselves all those decades ago – and must at least in part reflect how those four musicians each saw themselves.